Solar energy systems ramp up in Tampa Bay Area

Taking advantage of tax incentives and reduced costs, private industries and power companies are switching to solar as a more efficient source of energy in the Tampa Bay Area.

Tampa Tank Inc.-Florida Structural Steel, a large industrial manufacturing facility at Adamo Drive and U.S. 41, flipped the switch last Friday on its new, 507-kilowatt solar system. The largest industrial photovoltaic system of its kind in Hillsborough County, it will enable TTI-FSS to meet 60 percent of its on-site power needs with solar energy.

“Tampa Tank is a large user of power. It was an opportune place to put a large installation,” says David Reed, a shareholder and board member. “It makes financial sense because of the savings we’re going to get on the power, the ability to now lock in costs and very predictable power over a long period of time.”

Added to that are federal tax credits, which makes the installation “very financially appealing,” he says.

It is the first solar project developed by TTI-FSS’s landlord, Hyde Park’s Shepard Capital Partners, of which Reed is a principal. The system represents a “significant investment,” Reed says.

“We think this is good for the community as well as for us. It’s really a win-win for everybody,” Reed says.

The solar installation, which covers most of the TTI-FSS’s roof, is expected to pay for itself within five years through energy cost savings, a 30 percent-of-the-cost federal tax benefit, and accelerated tax depreciation. TTI-FSS’s energy costs are expected to drop from 13 to three cents a kilowatt hour.

The installation is expected to generate power for 40 to 50 years.

Staying on the grid ensures a constant supply of energy even on overcast days. “If the sun is not shining, you’re not going to get the production you still need to be able to pull consistent power,” Reed says.

Tampa-based Solar Advantage, a solar and electrical contractor, did the installation. Martin Clewis, of Solar Advantage, says interest in solar energy has increased as the economy has improved. He does installations mainly for manufacturing and apartments.

“The problem [with solar power] has been with the price,” he acknowledges. “Technology has gotten a little bit better each year.”

Panels used to convert just 7 percent of the energy at its surface; now they convert up to 20 percent.

Solar power has a long history

In the 7th Century B.C., people used the sun to make fire and burn ants with a magnifying glass, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. By the 1st to 4th centuries A.D., they were relying on the sun to heat Roman baths. But it wasn’t until 1954, when Daryl Chapin, Calvin Fuller and Gerald Pearson invented the photovoltaic cell, that people were to capture enough of the sun’s energy to run common electrical equipment.

Still, the early solar panels didn’t work well, and cheaply, enough. People struggled to find ways to harness the sun’s energy on a massive scale. High costs have kept people dependent upon coal and petroleum, even when they might prefer clean, renewable power readily available from the sun.

But now improved technology, reduced costs and financial incentives are convincing many to invest in solar power. In the third quarter of 2016, people were installing solar photovoltaic solar systems at the rate of one megawatt every 32 minutes in the United States, the Solar Energy Industries Association says. That’s a total of 4,143 megawatts, which broke previous records according to GTM Research and the SEIA.

Average costs for a photovoltaic system have dropped 33 percent since 2011, according to GTM Research and SEIA data.

Meanwhile government incentives are encouraging the switch to solar through tax credits. “I think people feel an urgency in regards to the tax credits,” Clewis says.

SEIA is working in the Florida Legislature to make going solar even more attractive. The goal is exempting homeowners from additional taxes associated with solar installations, says Sean Gallagher, SEIA’s VP of State Affairs.

Senate Bill 90, by Jeff Brandes, R-St. Petersburg, would prohibit land values derived from a “renewable energy source device” from being used in tax bill calculations.

A home installation may cost roughly $20,000 for 7 kilowatts, according to Tampa Electric Co. estimates. It may take 10 years to recoup the investment. You can learn more here. https://energy.gov/savings/residential-renewable-energy-tax-credit

Utilities investing in solar power

Utility companies are interested in solar too. In the Tampa Bay area, TECO has invested more than $50 million in solar energy since 2000. “The price of generating solar power is trending downward. It’s becoming more affordable,” explains Cherie Jacobs, spokesperson for Tampa Electric.

More than 1,000 of its customers have solar panels interconnected to the grid, she says.

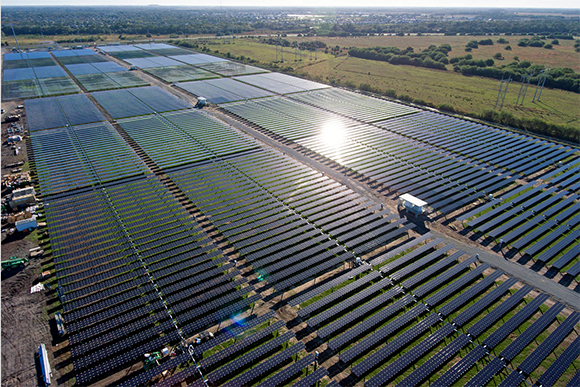

In Hillsborough County, TECO announced the completion of the largest solar installation in the Tampa Bay area in mid-February. Its 23-megawatt photovoltaic array, at 106 acres on its Big Bend Power Station in Apollo Beach, is also its first to track the sun. That allows the thin-film solar panels to produce more than 30 percent more energy than fixed panels.

Tracking isn’t practical on rooftops or shade structures. Big Bend is also TECO’s first “ground-mounted utility solar project,” Jacobs says.

The new addition is expected to save up to 30,000 tons of carbon dioxide every year – the equivalent of removing up to 6,000 cars from the streets. At any moment, the installation can create enough power for nearly 3,300 homes.

It is the third large-scale solar project for TECO since 2015. The first was a 2-megawatt facility on the top of Tampa International Airport’s south economy parking garage, which can produce enough electricity for 250 homes.

“It is more cost effective for a utility to build a large solar array than for an individual home or business to install a smaller solar array,” explains Jacobs. “It’s an issue of size and scale and scope.”

TECO also recently added a 1.8-megawatt solar facility at LEGOLAND in Winter Haven, allowing it to provide shade and generate power at the same time.

Florida Power and Light Co. announced plans Feb. 20 to accelerate the addition of new universal solar power plants, opting for eight instead of four plants. The addition of more than 2.5 million solar panels by early 2018 is expected to save millions in power costs over their lifetimes.

Each new solar plant will have a capacity of 74.5 megawatts. Together their total capacity is nearly 600 megawatts, enough power for about 120,000 homes.

Construction is expected to start in the spring at sites across Florida, including Alachua, Putnam and DeSoto counties. Other locations have not yet been announced.

FPL, the largest solar energy generator in the state, recently completed a solar power plant at the FPL Manatee Solar Energy Center. A subsidiary of the Juno Beach-based NextEra Energy Inc., it also runs the FPL SolarNow array at the Palmetto Estuary Nature Preserve in Manatee County.

Duke Energy Corp., a Charlotte, N.C. utility serving parts of central and north Florida, will be building its newest universal solar power plant near Live Oak, east of its existing Suwannee River Power Plant. The plant will produce 8.8 megawatts, enough to serve about 1,700 average homes at peak usage. It expects to break ground in the spring and be in full operation by the end of 2017.

Being smart with what we’ve got

A study by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, in conjunction with DOE, found some 97.5 quadrillion British Thermal Units were consumed in the nation during 2015. About 59 percent was wasted.

The bulk of the energy was generated by petroleum, 35.4 percent, which is used for transportation and industry. Natural gas supplied 28.3 percent used for industrial, commercial and residential needs, as well as electricity generation. Solar energy supplied .532 percent.

A Tampa startup, COI Energy Services, is working to reduce waste through proprietary software it unveiled Feb. 20 at the University of South Florida. Described as the Uber of energy, COI is offering a fee-based service that allows business users to voluntarily reduce usages during peak demand times in return for financial rewards.

CEO SaLisa Berrien says refrigeration systems can become assets, much like cars do with the UBER transportation services. Taking a lot of them off line at the same time has a huge impact.

“When you turn off these things, or when you adjust the temperatures on these things, you are now looking like a power plant coming on line in aggregate,” Berrien explains.

The program acts like insurance for the grid while allowing participants to save on small cutbacks. “It’s just free money if you don’t have a need for lighting here and there,” explains Vinny Bhatia, COI’s Chief Product Officer.

COI is targeting small- and medium-sized business in the United States from its base at USF. It commemorated its first year of partnership with Tampa Bay Technology Incubator at the unveiling.

“We’ll eventually be global, but we’re starting with the U.S.,” Berrien says.

Those who develop renewable energy, like solar, can get reimbursed when they supply the grid. The company hopes to simplify what is often times a complex process.

“Everyone knows that rebates are out there. People don’t want to apply for them because it’s complicated,” she adds.

COI centralizes and simplifies the information exchange, says Berrien, who has more than 25 years of experience in the energy field.

“It [COI] is helping to protect our environment,” Berrien asserts. “You’re getting paid to do the right thing.”