James Beard winner Adrian Miller bringing lesson in history, culture to Collard Green Festival

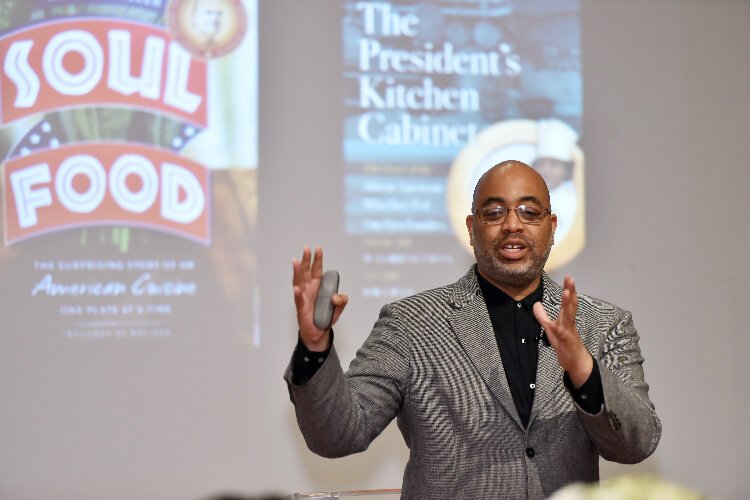

James Beard Award winner Adrian Miller is bringing a lesson in history and culture to three Bay Area speaking appearances for the annual Tampa Bay Collard Green Festival.

Celebrated soul food scholar and author Adrian Miller makes three appearances in the Tampa Bay area this week as part of the Tampa Bay Collard Green Festival.

Miller, a lawyer who served as an advisor to President Bill Clinton, has won the James Beard Foundation Award for Reference and Scholarship for two books, “Soul Food, the Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time”(2014); and “Black Smoke, African Americans and the United States of Barbecue” (2022). In between those two, he wrote “The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families, from the Washingtons to the Obamas” (2017).

Miller speaks at the University of South Florida on Thursday, February 15th; at the Cuban Club in Ybor City on Friday, February 16th; and he appears at the Collard Green Festival in south St. Petersburg’s The Deuces neighborhood on Saturday, February 17th.

A Denver resident, Miller is executive director of the Colorado Council of Churches. He talks with 83 Degrees about soul food, barbecue and presidential cooks.

Could you talk about President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s cooks in Warm Springs, Ga., where he would go to treat his polio?

Presidents usually arrived at the White House in poor health, and so they were often on a diet. FDR hated the White House food. I don’t know if you’ve heard stories about how horrible White House food was during his time.

He would go to Warm Springs to get treatments for his polio. He had two Black cooks cooking for him there, Lizzie McDuffie and Daisy Bonner. The First Lady or the White House physician would say, “Give the president this,’’ whatever the diet food was. And then as soon as they were out of the president’s presence, the cooks would bring the president what he really wanted… like pigs feet, Brunswick stew.

And Daisy Bonner cooked a souffle to serve FDR for lunch on the day he died?

He loved her food. So she timed this souffle to be served to him at 1:15, and he had his fatal cerebral hemorrhage at 1:10. She said that the souffle did not fall until he was officially pronounced dead, which was a couple of hours later. And anybody who has cooked a souffle knows that that’s a miracle.

Your talk at the Cuban Club Saturday night is titled “A Liquid History of the U.S. Presidency.’’ Is that liquid alcohol?

We’ll talk about Truman with old fashioneds. We’ll talk about FDR and martinis. We’ll talk about Theodore Roosevelt and mint juleps, which was a scandal in his time, whether or not he actually took a sip of a mint julep.

How did soul food become popular?

Basically, the 1960s with the Black power movement and some other things there was a consciousness added to what we would call soul food. So before, everybody called it Southern food or Southern cooking or just dinner. It generally didn’t get a name. The term soul food was floating around in Black culture in the ’40s and ’50s but it really became popular in the ’60s, and it was a way of bringing people together. So the concept of soul really distinguished the Black experience, so, really, it was soul music, soul brother and soul food.

This was news to white Southerners because they were being told that the soul food items were things that they couldn’t understand, and they had been eating the same stuff for a couple of centuries. So you get this divorcing where soul becomes Black and Southern becomes white. And we’re still dealing with the fallout of that today.

Even though the term was floating around, it was really the 1960s that this collection of food that became a standardized menu known as soul food, and, really, the book that I write is a reflection of that standard menu.

And what is the standard menu?

Fried chicken, fried fish, pork chops or chitlins as the entrees. Then you’ve got greens. The greens could be mustard, turnip, collard, kale, cabbage; blacks-eyed peas; candied yams; mac and cheese; some type of cornbread. Then a red-colored drink…. You would call it red drink (such as Kool-Aid). It just has to be red.

And then for dessert, you could have one of four. You could have pound cake, banana pudding, sweet potato pie. And peach cobbler.

Are Southern cooking and soul food often the same thing?

They draw on the same ingredients and techniques and traditions, but I think there is a difference. It’s really just in the way that the cuisine is performed. In soul food, there tends to be more of an emphasis on cheaper cuts of meat and bone-in meats. So it’s the difference between having a catfish fillet and having catfish bone-in. And then the lines between savory and sweet are often more blurred in soul food than Southern food. For example, sugar in cornbread in soul food… A lot of traditional whites will say if you add sugar to cornbread you’ve turned it into cake.

Researching soul food, you ate at 150 restaurants in 35 cities in 15 states. Some favorite places?

I really liked this place called Bully’s Soul Food in Jackson, Miss. It’s the kind of place where you walk in and there’s a table right off the dining room – pre-COVID – where they were peeling sweet potatoes and stripping greens.

Another place that I really liked, This place called Florida Avenue Grill in Washington D.C. It’s the oldest continuously operated soul food restaurant in the world.

How old is it?

1944.

Any place in the Tampa Bay area that you liked?

I was in St. Petersburg, I think it was a year ago, and I went to a place, I think it’s called Heavy’s (Heavy’s Restaurant and Take-Out in The Deuces neighborhood).

What is the history of Black barbecue pit-masters?

I argue that barbecue was Native American in its foundation, but then the interplay between enslaved Africans and colonizing Europeans starts to put what Native Americans were doing onto the road of what we now call Southern barbecue.

For a while enslaved Native Americans were doing this cooking, but then as more Africans get into the mix they were tasked with doing this work. We have to remember that early barbecue was very labor intensive. Somebody had to clear the area where the barbecue was being held. Somebody had to chop down the wood. Somebody had to dig the pit a couple of feet wide. Somebody had to butcher those animals and process them. Somebody had to cook them by flipping them continuously over the live coals, where the wood was… burned down to coals. And somebody had to swab it every once in a while to keep it moist. (A concoction of vinegar and spices was used.) Somebody had to cut that food up and serve it, and somebody had to provide the entertainment. And that was all enslaved African Americans.

It’s really not until the late 1800s that you start to see more white men getting involved with barbecue. By the time you get to at least the 1810s, 1820s, the notion is, if you’re going to have barbecue and have it done the right way you have African Americans involved.

And you’ll be talking about this during your appearance at USF?

I’m going to talk about this, I’m going to talk about how African Americans after emancipation became barbecue’s most effective ambassadors and took the taste of barbecue to places all across the United States. And in many cases, they kick-started the barbecue scene in places and really were barbecue’s go-to cooks until the 1990s, when all of a sudden you see a major shift toward white men as the best cooks of barbecue.

Colorado is not known as a barbecue or soul food state. Were you an aficionado?

I always lose street cred when I tell people I’m from Colorado. It’s a great migration story. My parents are from the South. My mom’s from Chattanooga, Tennessee. And my dad’s from Helena, Arkansas. So they independently came to Denver in the 1960s and met here and raised me in Black food traditions as well as Black cultural traditions.

You served as Deputy Director of the President’s Initiative of One America during the Clinton administration and you had access to the White House dining room. That was long before you decided to write “The President’s Kitchen Cabinet,” but did you hear any stories from White House cooks and servers?

No, this is my biggest regret. While I was in the White House I didn’t even think about this.

For event details and ticket information, go to Tampa Bay Collard Green Festival.