Partner Partner Content Before Water Street Tampa: A brief history of the Garrison Section of Downtown Tampa

Long before developers named Water Street Tampa, the waterfront property situated between the modern Tampa Convention Center and the Florida Aquarium enjoyed a rich history.

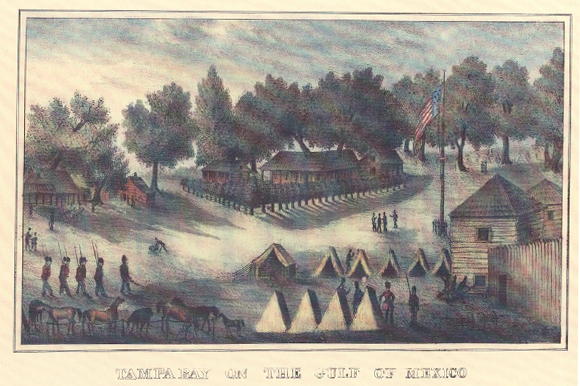

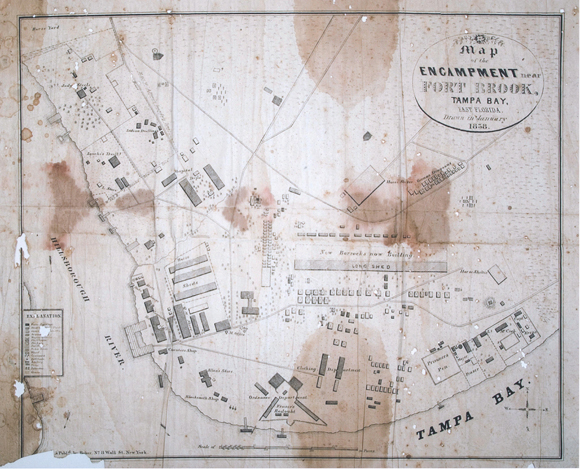

Much has been written about the new and exciting development covering more than 50 acres near Amalie Arena. Recently named Water Street Tampa, the area — which counts the Tampa Bay History Center as one of its neighbors — is undergoing a revolutionary redevelopment. The land included within Water Street Tampa, along with the property immediately to the west, has witnessed quite a bit of history. It was home to Fort Brooke, a U.S. Army fort from 1824-1882.

After the fort property was decommissioned by the War Department, there was a mad rush to see who could gain control. The Town of Tampa laid claim, as did a number of homestead applicants. Others simply moved onto the former fort property in an attempt to claim squatters’ rights. Litigation soon followed, and it included all of downtown Tampa south of Whiting Street between the Hillsborough River and today’s Ybor Channel.

The winners in the case were the original homesteaders of the property who applied for federal land grants when the U.S. Army decommissioned the fort in 1882. Legal maneuvering by many parties — including the Town of Tampa in the early 1880s and dozens of squatters who moved onto the property in the 1880s and 1890s — tied up the legal title until the favorable decision in September 1895.

The main homesteader was Elizabeth Carew, whose husband, Edmund Carew, filed for a homestead on the land ahead of Tampa officials who wanted to annex it into the town’s boundaries. Mr. Carew died before the conclusion of the court cases, but his widow kept pursuing the matter to the end.

Mrs. Carew was not the only homesteader attempting to defend their ownership. Three African-Americans also claimed and were awarded, property in what was known as the Garrison. Julius Caesar, Frank Jones, and a Mrs. Stilling all held smaller claims on the western end of the old fort property. They also shared the same attorney, Samuel J. Finley of Gainesville. The fact they retained a Gainesville attorney isn’t unusual given that the city was also home to the state’s federal land office.

There were approximately 100 people living in the old garrison section of Tampa when the court handed down its decision in 1895, and they lived within one of two different municipalities. One, the Town of Fort Brooke, was fairly organized and had its own mayor, police force, and local laws. The other, known as Moscow and led by a Russian immigrant doctor named Frederick Weightnovel, was anything but organized. Fort Brooke and Moscow were wide open places, both physically (the old fort property was mostly free of buildings but was covered in moss-draped live oak trees) and metaphorically (there were numerous of bars, gambling houses, and brothels across the Garrison).

Ushering in modern Tampa

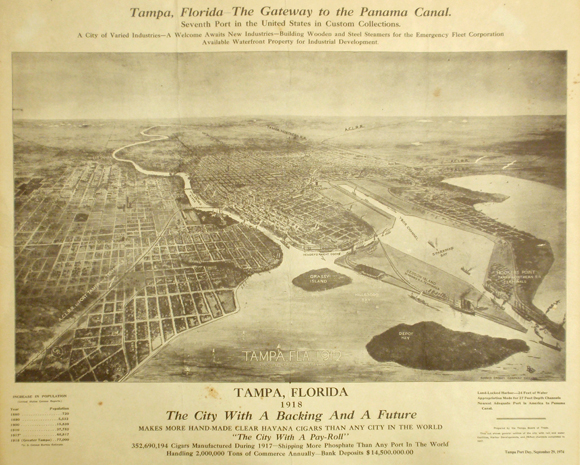

The idea of a large town park was very attractive to Tampa’s leaders in the early 1880s. This was Tampa before Henry B. Plant brought the railroad and V. M. Ybor and Ignacio Haya established the cigar industry. Both of those events ushered in modern Tampa, and the city that emerged from the 19th century saw its waterfront as an industrial or residential asset rather than an aesthetic one.

The Tribune described the Carew portion of the Garrison, which was located on the western side along the Hillsborough River and Hillsborough Bay, as “surrounded by spreading oaks, and commanding a beautiful view of the bay, it is perhaps the most eligible residential property in the city.”

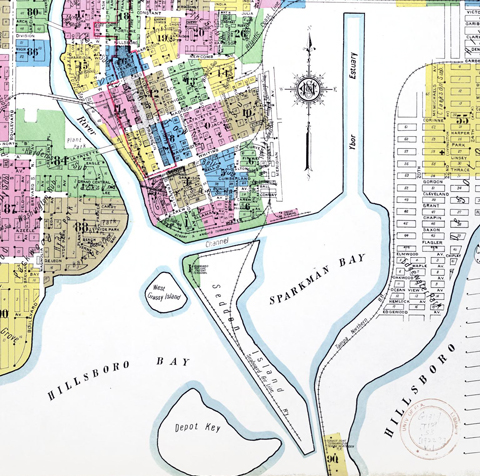

The rest of the approximately 160-acre property could be similarly described aside from the eastern end, which was known as the Estuary and consisted of low-lying land that occasionally flooded at extreme high tides. The Estuary land was at the center of a dispute between two rival railroads in the early 1900s and, through the efforts of U.S. Congressman Steven Sparkman, would become the western edge of the Ybor Channel and home to wharves and warehouses.

The area between the Carew property and the Estuary was owned by the three African-American homesteaders. A portion of that land, around South Nebraska Avenue, Caesar Avenue (named for property owner Julius Caesar), and Garrison Street (later renamed Cumberland Avenue), was home to one of Tampa’s black neighborhoods. Though small – the community consisted of a few dozen homes and some small businesses – it represented one of the few owner-occupied African-American areas in the city.

Finley, the Gainesville attorney who represented Caesar, Jones, and Stilling received a portion of the Garrison land as his payment for taking the claimants’ case. The Tampa Tribune described his fee as “a fat one” totaling “one-half the lands of his three clients for his trouble.” Finley moved his law practice to Tampa and branched out into land sales. He was involved in three separate platted subdivisions within the Garrison, all in association with his former clients – Finley and Caesar (filed Sept. 4, 1895), Finley and Stillings (filed March 24, 1896) and Finley and Jones (filed June 1, 1897).

The three subdivisions are contiguous, running south to north in order of plat date. Meridian Avenue traces its beginnings to these plats, serving as the eastern boundary of each. Other features that remain today are the railroad tracks to the west of Meridian plus three street names: Walton, Finley, and Cumberland. The origin of Cumberland is unknown, but Finley is certainly Samuel Finley and Walton is likely named for real estate agent John Walton.

While Finley and his partners worked on the eastern end of the Garrison, Mrs. Carew was making a few deals of her own. She partnered with the Hendry & Knight Company, who eventually played a large role in the development of the Garrison, to subdivide and advertise her property. Their early involvement was highlighted in the April 9, 1897, Tribune headlined “Garrison Improvements — Hendry & Knight Touch the Button, Presto! There’s a Change.” The article illustrated the changes: opening of Franklin Street south of Whiting to the water; the creation of Water Street that skirted the shoreline beginning at the western end and continuing along the southern coastline to the Estuary; and the extension of Grand Central (Kennedy Boulevard) “from the river on the west to the bay on the east.”

Seeking untapped wealth

Others also subdivided their parcels of land within the old fort. The family of William Bell, for whom Bell Street is named, fought a group of squatters and the Florida Central and Peninsular Railroad to keep title to their land. The Bells were victorious, and they filed the plat for Bell’s Subdivision, just south of Whiting Street and west of Nebraska Avenue, on March 1, 1899.

Carew and Hendry & Knight, and everyone else who owned property in the Garrison section faced one last lawsuit in 1901. The heirs of Richard Hackley, who originally claimed a huge section of land in 1818 through a Spanish land grant, filed suit to either take over the fort property or be compensated for their loss. Hackley lost his claim to the property in 1824 through the actions of Colonel George Brooke and James Gadsden, the founders of Fort Brooke, and his descendants lost their case in the U.S. Supreme Court 80 years later.

With the 1904 verdict against the Hackley family, titles to land in the Garrison were finally uncontested. The Hendry & Knight Company consolidated, as best they could, the various plats for the property into a master plat, which was filed in 1905. Included in that plat were “water lots,” lots that at the time were under water but that soon would rise from the shoreline and become dry land along the newly dredged Garrison Channel. The Tampa Convention Center, Marriott Waterside, Cotanchobee-Fort Brooke Park, the Tampa Bay History Center, Channelside Bay Plaza, and the Florida Aquarium all occupy land dating from that dredging project.

Any history of the Garrison would be incomplete without mentioning a story that appeared in the April 1, 1902, Tampa Tribune.

Declaring that oil had been discovered bubbling up in the old fort property, the Tribune stated that “the discovery means an independent fortune for each of the gentlemen” who had just purchased the property. The story was, of course, an April Fool’s joke, but the sentiment may become anything but. The old garrison property certainly carries the potential of an untapped oil well.

Rodney Kite-Powell is the Director of the Touchton Map Library and the Saunders Foundation Curator of History at the Tampa Bay History Center. He welcomes your questions and comments and can be reached by email, or by phone, (813) 228-0097. Support for publication of this column comes from the Tampa Bay History Center.