Tampa community leaders consider how best to memorialize local men killed in lynchings

Public input and letters of support for honoring the victims of lynchings in Tampa and Hillsborough County will be gathered from the community at large including chambers of commerce, governmental bodies, churches, mosques, and synagogues.

Their names are barely remembered. History records very little about them except their last day on earth.

Adam. Galloway. Lewis Jackson. Samuel Arline. John Crooms.

Each of these men died in Hillsborough County at the hands of racist mobs who lynched them for one reason — they were black.

Now a grassroots campaign hopes to memorialize these men, as well as Robert Johnson, with two historical markers. One would be a marker relocated from a six-acre memorial park created by the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama. The second would be a Hillsborough County initiative for Johnson who was dragged from jail and murdered, probably around 50th Street and Hillsborough Avenue in 1934.

“It’s potent in a moral sense,” says Tampa City Councilman Luis Viera. “We had this in Hillsborough County, and I didn’t know it. There’s a lot more that people don’t know. I think it’s the right time for it. We’re reaching out. We’re reaching out.”

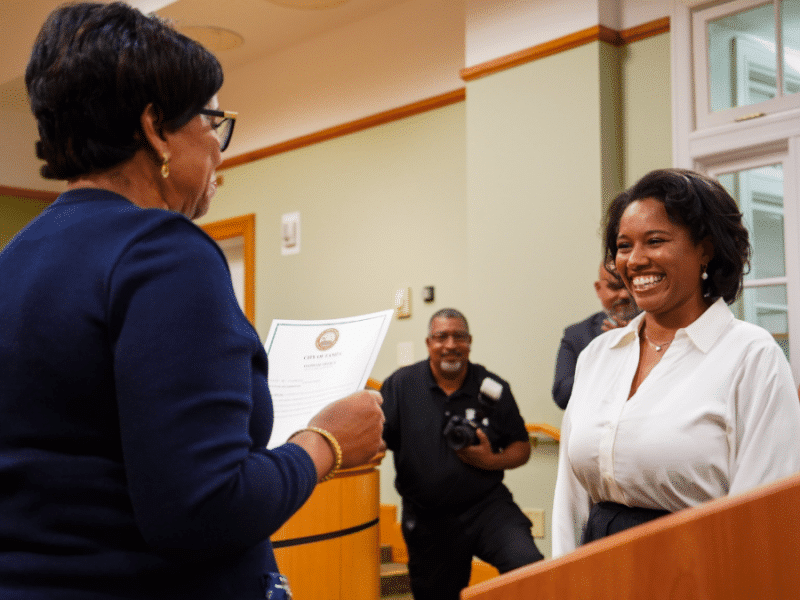

Viera visited EJI months ago and came away believing that the Hillsborough community has a responsibility to acknowledge this terrible history of racial injustice. He reached out to State Rep. Fentrice Driskell, and Stetson civil rights law professor Tammy Briant Spratling who heads up Community Tampa Bay.

Together they explored how to proceed in a way that could bring the community, black and white, together. Initially, a small group of people met at Allen Temple A.M.E. Church, a historically black church in Tampa Heights. Among the members are local historian and tour guide Fred Hearns, NAACP President Yvette Lewis, justice reform advocate Debbie Wells, businessman Stanley Gray, attorney Ron Weaver, attorney John Schifino and Allen Temple’s Pastor Glenn Dames, Jr.

At the most recent meeting on Jan. 7, about 20 people — black, white, and Hispanic — met to discuss the next steps.

Among the priorities is a series of community meetings across Hillsborough to gather public input and consensus on the project.

“This project is not top-down; it’s bottom-up,” says Viera.

Welcoming everyone to the table

Driskell is encouraged by the diversity and growing number of people who want to participate.

“This is exactly what we want this to be,” she says. “It has to have community support.”

The group recently sent an initial inquiry to EJI about its Community Remembrance Project. Public service attorney Bryan Stevenson founded EJI to advocate for racial justice and reform. The nonprofit also seeks to foster dialogue about racial injustice and to ensure that victims of systematic racial terror are remembered, not forgotten.

Stevenson is executive director of EJI and author of “Just Mercy,” a chronicle of his successful efforts to free Walter McMillian, wrongly convicted of killing a white woman.

More than 4,000 lynchings, from Reconstruction to the 1950s, are documented in an EJI report “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.”

Florida had 331 lynchings, earning the sad distinction of being second in per capita lynchings of 12 Southern states included in the report.

New data looking at additional states increased the number of documented lynchings to more than 4,400, according the EJI website.

More than 800 steel monuments at EJI’s National Memorial of Peace and Justice honor the men, women, and children who were lynched. Historical markers for every county also rest within a six-acre park, surrounding the memorial. EJI hopes eventually every county will claim its marker and begin a local dialogue of reconciliation and truth-telling.

Before allowing markers to be relocated, Spratling says the nonprofit wants to know there is local “buy-in” for this effort.

In addition to community meetings, a bus tour to Montgomery is being considered as well as a website dedicated to the project.

Letters of support also will be gathered from the community at large including chambers of commerce, governmental bodies, churches, mosques, and synagogues.

“If we don’t deliver the message correctly, people are not going to respond to it,” says Yvette Lewis, president of the Hillsborough chapter of the NAACP.

Hearns hopes to see schools expand history lessons to tell the stories about lynchings “so we have some education for students.”

Learning from the past

Spratling puts education into practice each year with a civil rights bus tour for students to historical sites in the South. One of those tours stopped at EJI.

Confronting the past is vital, she says.

“It raises the visibility of these victims,” Spratling says. “Their stories have been untold. What happened to them was outside the legal process. They haven’t had the privilege of having legal records.”

It is also true that communities knew these lynchings were taking place, sometimes as hundreds gathered in a “carnival” atmosphere as witnesses, she says.

Too few people are willing to admit this is part of Florida’s history, Hearns says.

“We need to open minds to the truth and conviction that they will no longer hide this chapter of history undercover,” he says. “This was terrorism.”

But there is value in being truthful and recognizing these men who were lynched is one step, he adds. “When you know better, you do better.”

The next community meeting will be at 6:15 p.m. on Feb. 4 at Allen Temple A.M.E. Church, 2101 Lowe St.

For more information, visit the Equal Justice Initiative website.