Tampa Bay area cities drink up innovative water solutions

Sustainable water conservation projects are underway in Tampa, Clearwater and St. Petersburg, where projects designed to meet future demand can treat both reclaimed fresh water and brackish saltwater to be safe and drinkable.

Tampa Bay isn’t experiencing the record-setting drought that is straining resources in California. There Gov. Jerry Brown is ordering a 25 percent cut in water consumption and calling for heavy fines for wasting water.

But that doesn’t mean the region or Florida can afford to be complacent about water conservation.

According to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, anticipated population and industry growth in Florida will increase demand for water by an additional 2 billion gallons daily by 2025.

“All across the world, the shortage of a water is an increasing problem. People are looking at alternative sources to meet the demand,” says Tracy Mercer, director of public utilities for the City of Clearwater.

Novel solutions here at home

The cities of Clearwater and Tampa are both looking at novel solutions to balance the region’s continued economic growth and quality of life against any concerns posed by water availability or price.

Clearwater’s unique, first-of–its-kind project gives the city a national leadership role in water conservation.

Titled the ground water replenishment project, or aquifer recharge, the plan calls for improving water levels in the aquifer by using reclaimed water that’s been purified to higher than drinking water quality.

“The goal is to replenish the aquifer by adding up to 3 million gallons of ultra-pure water a day,” says Mercer. “It’s like banking water for the future.”

Clearwater gets most of its drinking water from the Floridan aquifer, a vast underground rock formation of shell and limestone that lies under all of Florida. The rock formation holds water – fresh water flows through the upper portion and salt water is found at a deeper depth.

While there is no immediate concern about this natural resource not being able to supply fresh water needs, Mercer points out that it is a limited resource.

“There needs to be a balance between water withdrawal and aquifer replenishment, and the need to protect it from salt water intrusion into the upper layer of fresh water,” says Mercer. “We realized we needed an integrated water management strategy that would preserve our supply of drinking water.”

City officials have turned to reclaimed water as a possible solution.

A sustainable water resource

“Residents and businesses purchase water, use it once to drink or shower, and then it comes back to us, where it’s turned into reclaimed water for irrigation,” says Mercer. “We realized this could be a source of water once it’s purified to meet all health and sanitation standards.”

And, unlike rivers, lakes, rainfall or even the aquifer, reclaimed water won’t be affected by a drought, says Mercer. It’s an untapped resource.

Although a number of groundwater replenishment projects have been developed around the country, including several in Texas and one in California, none are similar to the concept proposed by Clearwater — filtering it through the aquifer to serve as a future sustainable water source, says Mercer.

Not all of Clearwater’s reclaimed water would be treated. Some would still remain available for irrigation. The remainder will be diverted to a water purification plant where a several step, high-tech process removes all unwanted compounds, including nitrogen and phosphorus. These are the nutrients that make reclaimed water so beneficial to the landscape, but are harmful if found in drinking water.

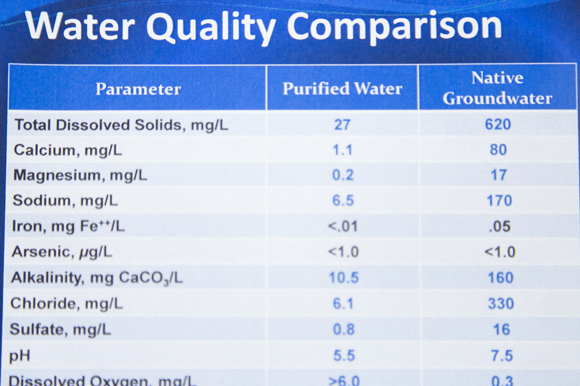

Once the water has been filtered and purified, it would be treated one final time so it is a better match with the mineral content of the groundwater, says Mercer.

Almost ready to go

A one-year pilot evaluation, which concluded last year, successfully demonstrated that the project was safe and could exceed guidelines for water quality. Public forums were held to explain the project to local residents and businesses and to dispel concerns.

The next step is to obtain the necessary funding to build a full-scale water purification plant and a groundwater recharge well system, says Mercer.

A pipeline from the water purification plant would deliver the purified reclaimed water to five or more “recharge” wells on city owned land. The wells connect to the aquifer and would allow the now-clean reclaimed water to naturally “percolate” up to the fresh water supply.

“We hope to begin construction some time this year and be online by 2017,” says Mercer. The estimated $29 million in funding for the project will come from the City of Clearwater with grant support from the Southwest Florida Water Management District.

Tampa also looks to reclaimed water

Tampa is also exploring using reclaimed water to boost the city’s future water supply, but in a different way than Clearwater.

The project would take a portion of the city’s reclaimed water to replenish the Tampa Bypass Canal, a 14-mile waterway that was built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the 1960s and ‘70s.

The canal provides flood protection for nearby communities by diverting water as needed from the Hillsborough River. It also serves as a water supply source for Tampa. It’s located near Fletcher Avenue and U.S. 301 in northeast Tampa.

“The Hillsborough River is our primary source of water, but the Tampa Bypass Canal serves as a back-up, especially during the dry season from March to June,” says Brad Baird, administrator Public Works and Utility Services for the City of Tampa.

The project would divert a portion of the city’s reclaimed water from the Howard F. Curren Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant near the Port of Tampa to wetlands and sandy rapid infiltration basins on land owned by the Southwest Florida Water Management District (SWFWMD).

The SWFWMD land – some 1,638 acres – is adjacent to the Tampa Bypass Canal area.

Natural filtration

Unlike Clearwater’s plan that uses technology to purify the reclaimed water, Tampa’s project would rely on nature to do the job, says Baird.

An underground pipeline would connect the Curren treatment facility to the SWFWMD wetlands, where the water would slowly filter through the ground, allowing impurities to be removed naturally over time.

“We’re looking for partners and we’ve applied for funding,” says Baird. “We’re on the list of potential water projects to be voted on in Tallahassee.“

The estimated $260 million project still requires permitting from regulatory agencies, including the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Southwest Florida Management District, Hillsborough County Environmental Protection Commission and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

It also needs extensive research and analysis, including building a small-scale model to measure everything from how many nutrients the wetlands can remove, to how many acres of wetlands would be needed and how much reclaimed water would be required to give sufficient yield.

“We hope to know in about two years if this is a viable project for us to move forward on,” says Baird. “If it is, then it will be about seven to nine years before we complete the various phases and are ready to go.”

Salt water to drinking water

In addition to recharging the aquifer with purified reclaimed water, Clearwater is transforming brackish or slightly salty groundwater into drinking water using reverse osmosis technology.

The city held a ribbon-cutting ceremony the first week of June to announce the launch of its second reverse osmosis water treatment facility. The first one opened in 2013.

Reverse osmosis removes dissolved particles, minerals, salts and ions to purify the water and make it safe to drink.

“We expect to produce up to 6.26 million gallons per day of additional drinking water using this method,” says Mercer.

Reverse osmosis technology is not new to Tampa Bay. The Tampa Bay Desalination Plant uses this technique on seawater.

The TECO Big Bend Power Station withdraws some 1.4 billion gallons of saltwater from Tampa Bay to cool its operations, and then discharges the water, now clean and warm, back to the bay.

This is the site of the Manatee Viewing Center in Apollo Beach where manatees love to congregate in the winter.

About 44 million gallons of the seawater are captured by the desalination plant and run through reverse osmosis to create some 25 million gallons per day of drinking water.

Ongoing water conservation measures

Fortunately cities in the Tampa Bay region have long had water conservation initiatives in place, including educational campaigns to help raise awareness about how to reduce consumption, rules on watering restrictions for lawns and programs that encourage reclaimed water use for landscape irrigation.

In fact, St. Petersburg was the first city in the U.S. to introduce an urban reclaimed water program, when it was implemented in the 1970s. St. Petersburg’s program continues to be one of the largest in the world, with more than 37 million gallons per day going to keep homeowners’ yards, golf courses, city parks and the landscape around commercial businesses green.